Laureate for Irish Fiction Anne Enright Talks Gay Marriage, Writing about Family, and Being a Female Author in Ireland

by Megan Wessell

Megan blogs about books at A Bookish Affair.

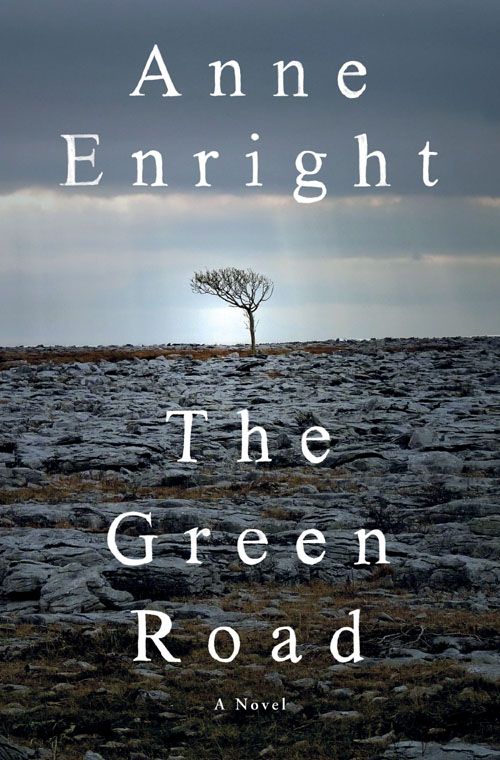

As far as Gaithersburg Book Festival 2015 featured authors go, Anne Enright almost wins the award for the author who will be traveling the furthest. She hails from Ireland. As excited as we are to have an author come so far, this is not her only accomplishment by far! Ms. Enright was recently named the very first Laureate for Irish Fiction. She also won the 2007 Man Booker Prize for Fiction for “The Gathering.” We are thrilled to have the honor of welcoming her to our book festival to discuss her latest book, “The Green Road.”

“The Green Road” is the richly detailed story of the Madigan family. Set over thirty years, this book follows Rosaleen and her four children spread throughout Ireland, the United States and West Africa. Rosaleen has a definitive idea as to how a family is supposed to be and how a family is supposed to act. She cannot understand how her children could feel differently. So when one son, Dan, makes a stunning announcement at Christmas, Rosaleen’s thought of perfection is shattered. Not only is there a compelling story but the writing of the book is wonderful! The way that Ms. Enright writes the characters truly brings them to life effortlessly. At its core, this book is about what it truly means to be a family even when things do not go as planned.

Below is an excerpt from a Q&A that Ms. Enright completed for her publisher.

The gay marriage referendum is coming up in Ireland later this year. How do you feel your book speaks to this ongoing issue?

I have a character in the book who is gay, and I tried to stay true to the path he would take through life: it wasn’t something I had complete control over, to be honest. Dan decides to get married—despite his difficulties loving his partner (or loving anyone, indeed)—and his sister is almost disappointed. “I thought you got away from all that,” she says, meaning the great heterosexual institution of marriage. “I did get away from it,” he says. “And now, I can do what I like.”

Perhaps this reflects my own view as much as it does Dan’s. People have great difficulties, they come through huge and wonderful personal battles, in order to become proper human beings who can love other human beings. I think that’s all there is, really. In my own (heterosexual) case, marriage was not about giving in to conservative values but about radicalizing them and making them new.

Your book deals very delicately, and honestly, with the AIDS epidemic. Was this section particularly challenging to write?

Like many people in the arts, I knew people who were HIV positive and I lost people—or we lost people—to the disease. There was a feeling, in the early 1990s, that we were living through astonishing times, but this great sadness, which was both historical and deeply personal, has not made it into many novels. I wanted this chapter to be about love, because I remember a time of great love and of great courage. I did not want all that to be forgotten. I don’t know if it was challenging to write; it was certainly deeply felt.

Can you describe your novel, “The Green Road”?

Four children grow up and move away from their childhood home in the west of Ireland. They go everywhere, have full, interesting, and complex lives, and then, in 2005, their elderly mother declares she is going to sell the house. So they all troop back for their Irish family Christmas and try to sleep one last time in their old beds. They bring their inner child home with them, only to meet their outer mother, Rosaleen: a woman who is sometimes wonderful and always difficult. The book is about compassion, how the heart gets smaller as we age, and how we try to fix that, if we can.

Your books often revolve around family. Why?

Actually, “The Gathering” was, for me, about memory and history. The large family in that book also begged large questions: if your birth was an accident, then what did your death matter? For me, the family is just a natural space in which to think about the big issues.

I suppose “The Green Road” is more “about” family than my other books, though I thought I was just using the family space to think about compassion and selfishness, about feelings of abandonment and of connection, exile and return. One of the things I like to do is to take that very male tradition of “lonely,” dissociated or bleak writing and I add in a mother. I do this because mothers are so absent in heterosexual male fiction—so impossible, somehow—and I am interested in working with this sense of “impossibility.” Psychology talks about nothing but the mother, the novel talks of everything but her. It is not just that I myself have a mother (funny, that), but that I am a mother. I am an Irish Mammy. Hurrah!

You once said “the periphery has always been a more interesting place for me.” Can you explain?

You once said “the periphery has always been a more interesting place for me.” Can you explain?

When I started out at the age of 20 or so, I thought that female fiction was going to be the most exciting thing ever. Things were opening up; there was so much to say that had not been said before. In fact, there was no huge welcome for the female voice in Ireland; the male tradition continued to dominate for the next 30 years of my writing life—and 30 years is a long time. I came to revel in my role as an outsider and also to dislike it. These are the tensions that, if they don’t kill your work, make it more interesting. I decided it was more interesting to be on the edge of things. And it is. But this was a decision I was obliged, somehow, to make.

Things have shifted with the generation of Irish writers that has emerged since the economic crash, in the last five years or so. I think there is real change in the air now. And I was recently made the first Laureate for Irish Fiction so I can hardly claim to be excluded—outside, with my nose pressed up against the glass. “The Green Road” is less “edgy” in some ways than my other work: there is more of a sense of scope, of shifting from one to another character’s point of view. Perhaps it was time to move in from the periphery and pitch my tent on the middle ground for once. Just for a while.